From “Griaß di” to “Baba”: if you want to communicate in Austria, you’ll often need a lot more language prowess than just the basic vocabulary from your last German lesson. Although the country is small, there’s an astonishing variety of dialects with fluid transitions in the border regions of the different federal states. From Lower Austria, Burgenland and Vienna in the east to Tyrol and Vorarlberg in the west – we’ll tell you what makes the languages of the nine federal states so special, including some fun and helpful vocabulary.

What dialects are there in Austria?

In 1920, German was established as the official Austrian language without any further specification. However, this does not mean that Austrian has no linguistic differences to Swiss High German or the High German commonly spoken in Germany. Differences can be found not only in grammar, pronunciation and spelling, but of course also in common idioms and words. A considerable part of the standard Austrian vocabulary originates from the languages of the former Habsburg Empire, as well as migration and intercultural exchanges.

| Did you know? There are different dialect families in Austria. While the majority of the country speaks a Middle Bavarian dialect, the Vorarlberg dialect is Alemannic – and therefore more closely related to Swiss German than to other Austrian dialects. To find out more, read on! |

Currently, however, traditional dialects are on the decline: Just 60-70 years ago – even in the immediate surrounding areas of Vienna – people still spoke a strong dialect that sounded like a completely foreign language to city dwellers. Nowadays, it’s more common to speak High German, especially in cities and amongst the younger generations. Even youngsters who grew up speaking their local dialect regularly switch to Austrian High German depending on the person they’re talking to.Social media and mass media are another factor that directly affects the relevance of dialects in modern-day Austria. Dialects are no longer limited exclusively to specific regions, with boundaries becoming increasingly blurred, and mixed dialects emerging. Nevertheless, there are still plenty of distinct linguistic characteristics in all federal states – here, we’ll take a closer look at each one of them.

Viennese

Historically, Viennese is the dialect that perhaps has changed the most – just like the city itself. As Vienna is located directly on the Danube, the city became an important trading centre several centuries ago, where people from different regions speaking different languages came together. To this day, the influences of these cultures can still be heard in the Viennese language. The Franks, for example, brought with them a special feature of Viennese – the so-called monophthongisation. This means that certain double sounds are merged into one. One example is the word “Haus”, where the pronunciation of /hɑɔs/ becomes [hɒːs]. These monophthongs are also clearly elongated, which is often perceived by outsiders as “grunting” or whining. This characteristic stretching of the vowels can be found, for example, in words such as “Stàà” instead of “Stein” and “I wààß” instead of “Ich weiß”.Many micro-geographical differences, such as the “Meidlinger L“, which originated within the working classes of Vienna’s twelfth district, can now be found throughout the whole city. If you’d like to speak genuine Viennese, then these terms are a good place to start:

- Blitzgneißa: quick thinker, usually meant ironically

- Gfrast: bad child

- Gigara: horse

- Grant: bad mood, anger, frustration – varies by context

- Kiwara: policeman

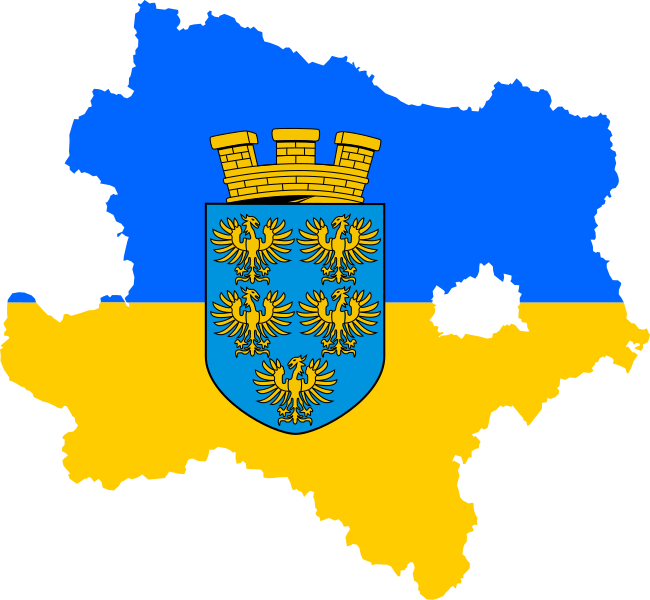

Lower Austrian

In Lower Austria, the country’s largest federal state, there are small regional linguistic differences. For example, even though the two towns are actually only 90 minutes apart, people speak differently in Melk than in Mistelbach.

The dialect in the Waldviertel sounds harsher, with clear Bohemian-Slavic influences. The Mostviertel, on the other hand, is known for its “oa”-sounds, where “heisst” becomes “hoast” and “kannst” becomes “kaunst”. In the Weinviertel, the so-called “Ui dialect” was spoken until around 50 years ago, where “Da Bui huit de Kui” is said instead of “Der Bub holt die Kuh” (English: “The boy is getting the cow”). In the industrial district, the dialect has flattened considerably due to industrialisation, as well as the proximity to Vienna – which can be distinctly heard in the pronunciation.

If you’re looking to strike up a conversation in Lower Austria, the following words are a great starting point:

- Dunaweda: thunderstorm

- gschamig: shy, unsure of oneself

- leidscheich: doesn’t like crowds/larger gatherings

- Ribisln: currants

- Zwutschgal: toddler

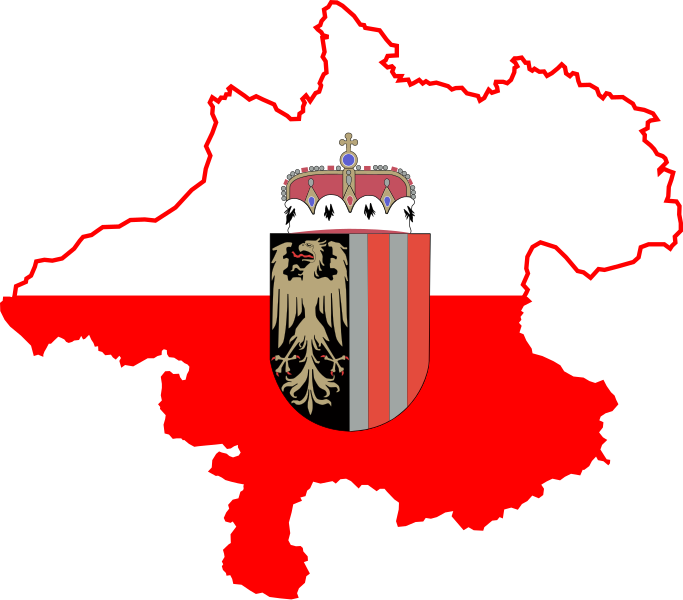

Upper Austrian

The regional languages of Upper Austria can be divided into three sublanguages: Innviertlerisch, Mühlviertlerisch and Traunviertlerisch – that is, the dialect spoken in the Innviertel, Mühlviertel and Traunviertel respectively. Depending on the region, a single word can sound completely different – the word “spielen” (English: play), for example, can be pronounced either as “šbün”, “šbuin” or “šbin”.

What unites the Upper Austrians, however, is the rounding of suffixes containing an I. For example, Nebel (“fog”) becomes “Nöwö”, Himmel (“sky”) “Hümmö”.

This is how they speak in Upper Austria:

- Flessal/Flesserl: traditional Upper Austrian pastry; yeast dough braided into a plait and sprinkled with poppy seeds

- goi?: added at the end of a sentence, comparable to “… isn’t it?” in English

- Klappal: sandals

- a Neichtl: a (little) while, comparable to “in a bit”

- schwanan: to lie

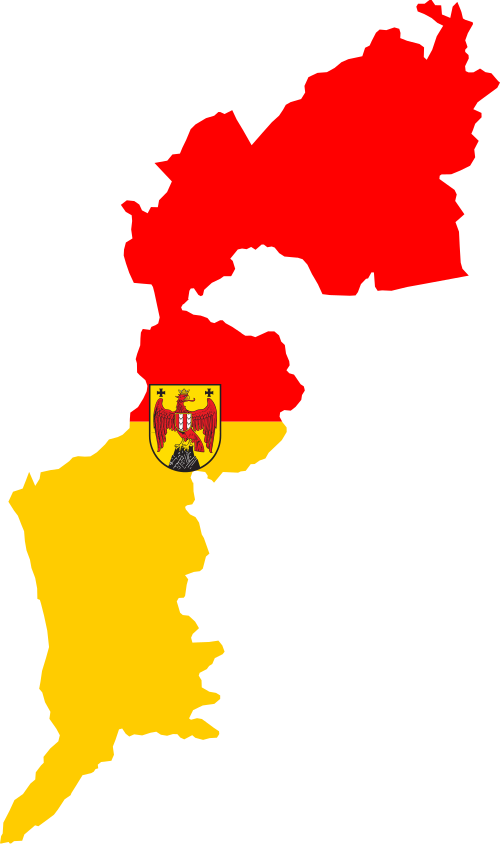

Burgenland dialect

Hianzisch, also known as “Ui”-dialect, is a dialect that was largely spoken in Burgenland, but also common in the Weinviertel region of Lower Austria. The dialect is so closely associated with Burgenland that at officials were even considering calling it “Heinzenland” when it was declared an official region in 1921.

Until around the 1970s, the “Ui”-dialect was the actual native language of the people in Burgenland, but was progressively replaced by the Middle Bavarian pronunciation due to job opportunities in larger cities. An example to illustrate this: “Mutter” (English: mother) changed from “Muida” to “Muada”. Hianzisch is still spoken occasionally today, but is nowhere near as widespread as it was a few decades ago.

Many sounds in the “Ui”-dialect are, as the name suggests, replaced with a “ui” sound. “Junge” or “Bub” (English: boy) becomes “Bui”, “tun” (English: do) becomes “tui”, and “genug” (English: enough) becomes “gmui”.

Some frequently used local words that can be found in Burgenland are:

- dauni: sideways

- Lodiridari: drilling machine

- Maibletschn: dandelion

- sakrisch: apt, on point

- Sumpa: big pot or idiot

| Did you know? One word, opposite meanings: “Zach” literally translates to “tough”/ “stiff”, and can be used to describe a piece of overdone meat, for example. In eastern Austria, however, it is mainly used among young people as a synonym for “tedious”, “unpleasant” or “uncool”, while in western Austria it has a positive connotation, replacing “cool”. |

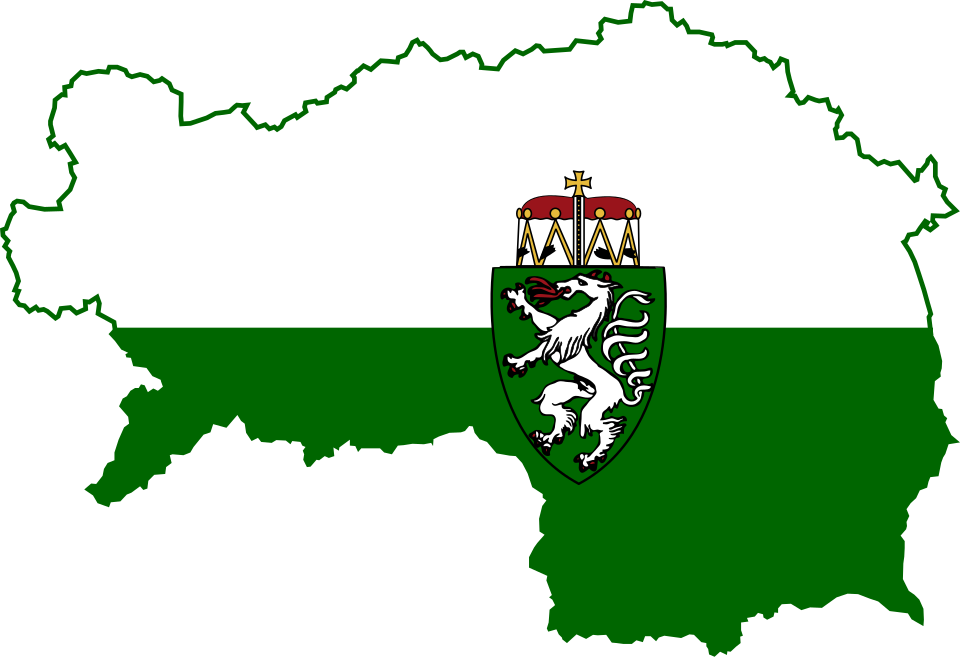

Styrian

Often the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of the Styrian dialect is the characteristic barking – or “Bölln”. Good examples of this peculiarity are the words “Öupfl” and “Söumml”: “Apfel” (apple) and “Semmel” (bread roll) in High Austrian German. Diphtongs – individual sounds that merge into a single syllable – can be found all over Austria, but no-one can even remotely compare to the Styrians. If you want to “bark” like a real Styrian, you should naturally use only authentic terms like these:

- brouckn: to pick

- kan Scheara: can’t be bothered

- köbln: to talk

- Schanti: police

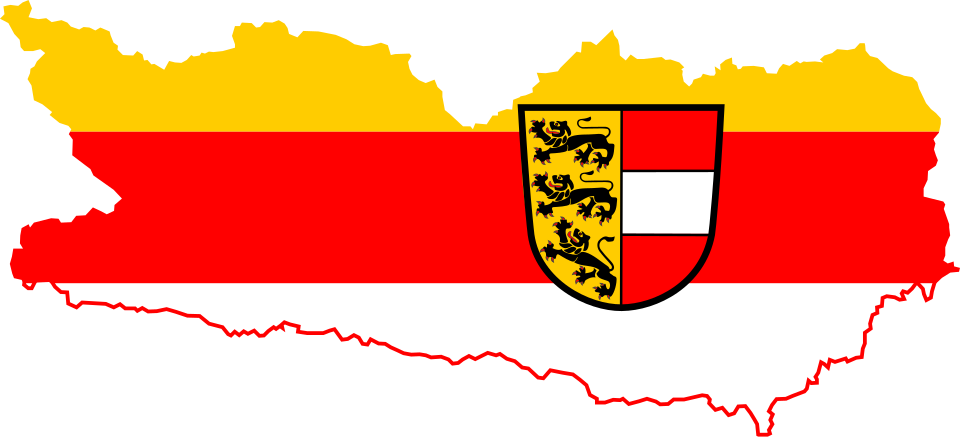

Carinthian

Carinthian can generally be divided into Upper, Middle and Lower Carinthian, although the regional boundaries are considerably blurred, particularly in border regions.

The proximity to the Slovenian border, for example, gave rise to the notorious “Carinthian stretch” – words such as “Wissen” (“knowledge”) and “Wiesen” (“pastures”)or “Ofen” (oven) and “offen” (open) are pronounced essentially the same. And of course there are many more linguistic peculiarities that characterise Austria’s southernmost province:

- The sounds “h” and “ch” are often interchanged – thus “sicherlich” (certainly) becomes [sihàlich], and “Mädchen” (girl) becomes [met-hen].

- Diphthongs such as “ei” or “au” are often pronounced like an “a”: instead of “Seife” (soap), “kaufen” (to buy) and “laufen” (to run), Carinthians say “Safn”, “kafn” and “lafn”.

- Carinthians also pronounce the I differently to the rest of Austria: “Geld” (money) becomes “Gölt”, “viel” (a lot) becomes “vül” and “schälen” (peel) becomes “schöln”.

Here are some words that are typically Carinthian:

- Bosnigl: a mischievous person

- Handsch: gloves

- Tschoda: hair

- Tuscha: bang, explosion, crash

- Strankalan: beans

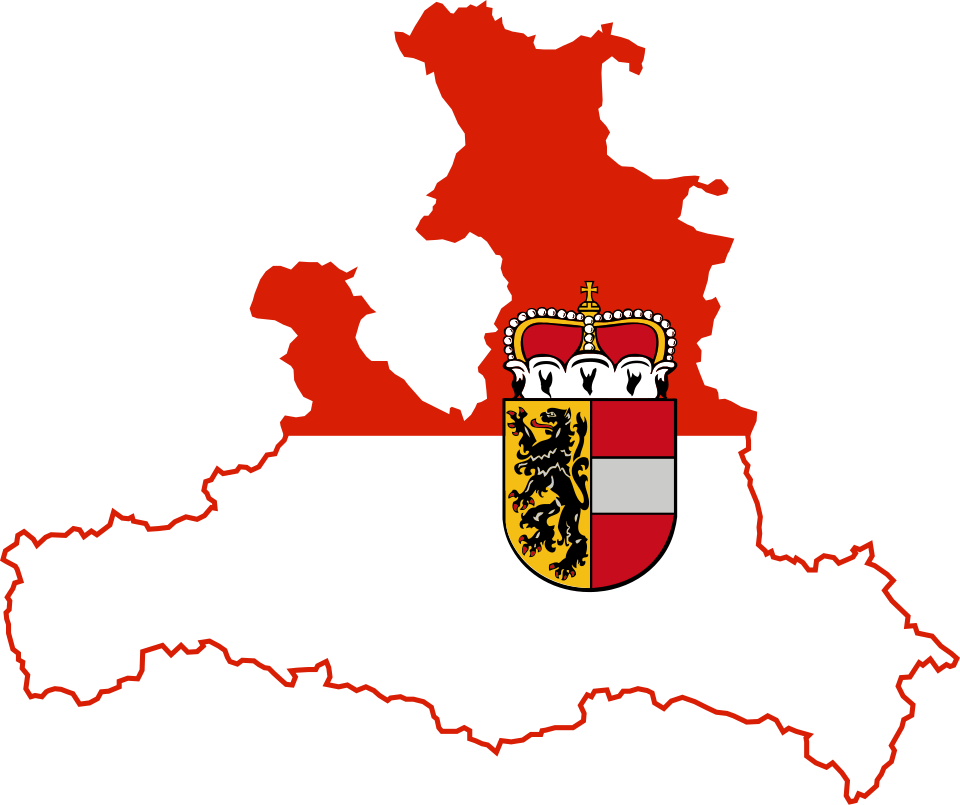

Salzburg dialect

From a linguistic point of view, the dialects in Salzburg are not a separate linguistic category, but a geographical one. They are complex mixtures of Middle Bavarian with influences from Tyrol, Carinthia, Bavaria and Vienna. As in the other federal states, they sound slightly different depending on the region.

A general characteristic of these dialects is that sounds such as p, t and k are weakened and become the sounds b, d and g. Examples include Bèch (Pech), Dåg (Tag) and Gnechd (Knecht) – or in English: “bad luck”, “day” and “servant”. However, if the K comes before a vowel, it stays a K. And if there’s an N at the end of a word, it is nasalised. As such, “kann” (“I can”) becomes “kôô” and “Mann” (“man”) becomes “Môô”.

Next time you’re in Salzburg, you can give these words a try:

- aizai: a little

- kasig: literally cheesy, meaning pretty, sweet (Salzburg)

- Kleezn: dried pears

- Manggai: marmot

- ninascht: nowhere (Salzburg)

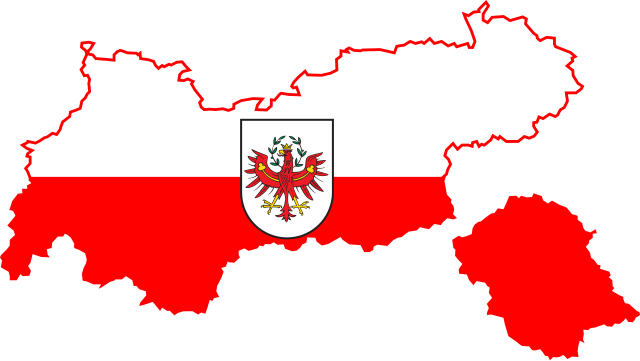

Tyrolean

Tyrol, like most of Austria, is part of the Bavarian dialect group and also has some Alemannic influences, especially in the west. Due to the dialectal origins, there are differences in the sounds, grammar and vocabulary. One example of different phonetics is the development of the word “mein” (“mein”), which was preserved in Alemannic as “mîn”.

The Tyrolean dialect is characterised by a high degree of linguistic diversity with strong regional characteristics, which, among other things, can be attributed to the remote location of the mountain villages. It has also been strongly influenced by migration, most notably by the Rhaeto-Romanic language group, Italian and, just like in Carinthia, Slavic languages.

Tyrol is particularly known for an “Sch” instead of a simple “S” and a hard “K”, which is pronounced more like a “kch” deep in the larynx. These peculiarities can easily be heard in the name of the capital, when the locals call it “Inschbrukch” rather than Innsbruck.

To speak like a real Tyrolean, these words will come in handy:

- aweck: away, gone

- detta: there

- gsi: been

- lei: only

- losna: to hear

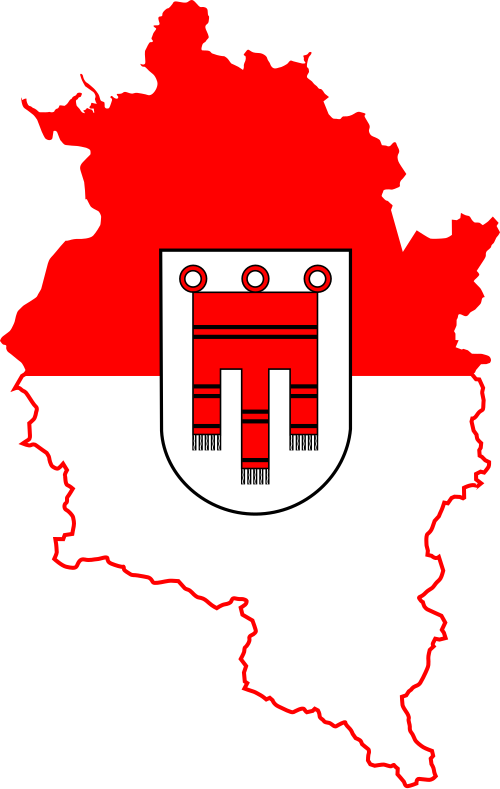

Vorarlberg

Vorarlberg is linguistically unique. Unlike the rest of Austria, the language is not a Bavarian dialect, but an Alemannic one, and therefore more closely related to Swiss German. A special feature is the frequent omission of the double sounds “au”, “eu” and “ei”. Thus, people in Vorarlberg say “Hus” instead of “Haus” (house), “Krüz” instead of “Kreuz” (gross) and “si” instead of “sein” (to be). Another difference compared to the other federal states is the absence of the word “war” (English: “was”). Instead, “gsi” (=”been”, Middle High German: “gesein”) is used – which is why the people of Vorarlberg are often called affectionately by their nickname “Gsi-Berger”. Despite all the similarities, there is no generally defined dialect Austria’s smallest federal state, but rather strongly regionally influenced dialect variations. The most striking can be found in Lustenau, in the deepest Bregenzerwald, as well as the Rhaeto-Romanic Montafon, while you’ll be able to catch traces of Swabian in Bregenz.

So if you want to make yourself understood in Vorarlberg, you can start with these words:

- Uf Wiederluaga: Goodbye

- gigagampfa: children’s seesaw at the playground

There are also words in Alemannic that sound outdated to the rest of Austria:

- des dünkt mi: that seems to me

- schlüfa: to slip (into)

- Häs: clothing

| Tip: Would you like to learn more about the Austrian language or improve your German language skills? At the Österreich Institut we offer a wide range of German courses for every language level from A1 to C2 – both for individuals, groups and companies. |

Austria’s dialect landscape is as diverse as the country itself: Whether it’s the famous Meidlinger L or the peculiarities of the Vorarlberg dialect, the local languages are deeply connected to the history and culture of our country. Want to find out more about the language, people and life in Austria as a whole? On our blog, you’ll find plenty of reading material to find out everything there is to know: from the most famous Austrian writers to typical Austrian customs and our best tips for learning German. Happy reading!